While I am much obliged to the New Yorker’s blog gremlins for linking my recent post on naked dudes and nuns, I must grumble a bit over their word choice. To wit:

Girls just want to have fun: surprising marginalia doodled by medieval nuns. [Emphasis mine.]

Put aside the issue of errant agency clause, ((It wasn’t the nuns that made the pictures of naked dudes. They were made for a nun, not by.)) because it’s the word “doodle” that really riles my pedantic dander. Granted, it’s not the first time that a marginalia post of mine has been disseminated to teh wider internets under the heading of “doodle,” ((And it probably won’t be the last.)) but it still irks me, because, as I try to make clear, the images I post here on Mondays ((Or on Thursdays and backdated to Mondays, as the case may be.)) weren’t scribbled into the margins by surreptitious snarkers whilst no one was looking. They were explicitly commissioned by the manuscript’s patrons as part of the project from the very beginning. For the well-heeled noble, ordering a book was not just a matter of selecting the text; deciding on size, presentation, illustration, and ratio of naked dudes to non-naked dudes in the margins was all part of the process of getting a book made.

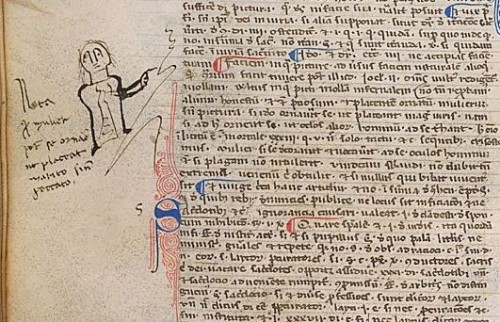

This is not to say that medieval readers and scribes didn’t ever doodle. It’s just easy to tell the difference between images planned as part of the manuscript’s commission and those scribbled in by a creative, bored scribe or one of the later owners of the manuscript. Just as you might imagine, a reader might decide a chunk of text was particularly important and make a note in the margin, like so:

Or, they might decide to play around in the blank space at the bottom of the page around one of the catchwords: ((A ‘catchword’ is a word or two placed at the end of a page or a quire to help make sure that the pages of a handwritten or (hand typeset) book are arranged properly when the book is bound. You match the word at the bottom of one page with the word that should appear at the top of the next. It’s particularly handy if there are multiple scribes working on the book simultaneously.))

Or, someone might just decide a page looked too blank and thus attempt to fill up some of that space:

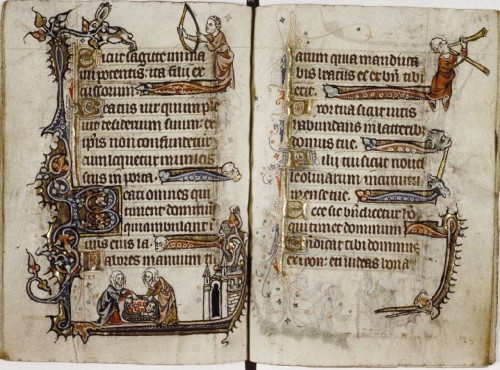

See, the thing about medieval doodles is they look just like modern doodles. They don’t look like this:

For this page, somebody sat down and sketched out a rough draft, showed it to somebody else, possibly even multiple somebodies. There were meetings. Consultants were brought in. The client was consulted. And at some point somebody said, “Yes, that’s very nice, the nuns smuggling that dude into their nunnery. Very topical. But I don’t like that blanket. Too drab. Can we get someone to put some flowers on it?” ((“And by the by, lose the poop in the monkey’s hand. We’ve already got three poop jokes in this sucker, and the countess warned us that she prefers sacrilege to scatology. Make it a rock or something. Still gets the point across, without the danger of fecal overload. Don’t worry, we’re doing a psalter for the Earl of Tewkesbury next month, and that dude is crazy for some poop-flinging monkeys and monkey hybrids. We’re going to need to double our order for dark brown pigment just to be safe.”))

The difference is, I hope, clear. You don’t doodle in gold leaf.