I feared I might have missed my chance to add to the Occupy debate, but this morning BoingBoing brought news that a judge has ordered the barriers removed from Zucotti Park, and protesters have returned. ((The first draft of this post originally had a self-effacing footnote here about how pathetic it was to get one’s news from BoingBoing, but so far (and it’s just after noon EST as I revise this footnote) the news has not made the front page at the NYTimes, Fox, CNN, or MSNBC.)) It would be customary for a medievalist blogger to beg apology for drifting off topic and into contemporary politics–but screw that. The way the debate has to this point been framed by Occupy’s opponents deserves the adjective I so often decry when used pejoratively by the press: medieval.

I feared I might have missed my chance to add to the Occupy debate, but this morning BoingBoing brought news that a judge has ordered the barriers removed from Zucotti Park, and protesters have returned. ((The first draft of this post originally had a self-effacing footnote here about how pathetic it was to get one’s news from BoingBoing, but so far (and it’s just after noon EST as I revise this footnote) the news has not made the front page at the NYTimes, Fox, CNN, or MSNBC.)) It would be customary for a medievalist blogger to beg apology for drifting off topic and into contemporary politics–but screw that. The way the debate has to this point been framed by Occupy’s opponents deserves the adjective I so often decry when used pejoratively by the press: medieval.

Put aside the question of whether “medieval” could accurately describe the things done to various Occupy protesters across the U.S., because my agenda is not so mundane as all that. ((Also because I do not wish to indulge in the use of medieval-qua-verbum that I so often decry, and because there really can’t be any argument that there’s not been an unfortunate amount of physical and mental brutality directed the protesters’ way.)) Rather, I say that the Occupy opposition’s frame narrative is medieval, because it relies upon many of the assumptions and ways of thinking that were current in England in the fourteenth century, a time we American medievalists tend to study obsessively.

We are so well-acquainted with England’s fourteenth century because it saw many things that we Americans today see ourselves in. The Peasant’s Revolt of 1381 we treat as an analogue of our glorious American Revolution; the proto-Protestant Lollard Heresy we see through the lens of our Purtian past and all those things about religious freedom we say we value; and Geoffrey Chaucer, who lived his sixty or so years right before the calendars all had to be flipped over to 1400, is almost an honorary American citizen at this point. ((As I believe I’ve discussed here before (more than once, even), when I teach Chaucer, my American students are always so ready to transmute his life into the familiar American fable of the misunderstood genius who revolutionized an unwilling hidebound culture, the shrewd entrepreneur with a revolutionary business plan who succeeded by realizing the foolishness of the way his competitors had done things before him.† The Middle Ages is always the hidebound foolish foil to our ingenious heroic avatars.

†And, yeah, it’s always a him doing the revolutionizing. Sorry, Betsy, you just get back to that flag-sewing, alright?)) We love the fourteenth century because we think it too familiar to really count as medieval. Instead it marks when Europe, finally anticipating the inevitable, reluctantly began to acquiesce to the coming American Century. ((The century that started around 1942 when Tom Hanks, John Wayne, and Will Smith stormed the beaches at Normandy and marched on together directly to Auschwitz to each single-handedly liberate those guys who went on to create Hollywood.))

Our fondness for the fourteenth ought to make us pause before denouncing the Occupiers, particularly if we recall what the people in charge were saying about our time-displaced brother revolutionaries during the Peasant’s Revolt. You may be familiar with the idea of The Three Estates, the way that medieval social thinkers described the natural division of medieval society. All of mankind could be divided into just three types of people: oratores, bellatores, and laboratores; those who pray, those who fight, and those who work, respectively–or to put it more directly, the clergy, the nobility, and everybody else who has to work for a living. Most Americans blanch at this division and align ourselves with those like our pal Chaucer who we say belonged to a rising Fourth Estate, the always already imminent middle class of idea men and merchants ((I forget which academic joked that the thing that unites all historians whatever century they study is that their century was the one in which the middle class first rose. Instead of helping me track down the reference, I’d prefer it if we just pretend I thought it up myself.)) that finally reached its apex and ideal form sometime around 1953 in Anytown, USA. ((Where everyone belonged to a cozy nuclear family whose breadwinner was an ad executive with a lovely wife who wore formal wear while vacuuming and minding their 2.3 rosy-cheeked children.)) But if we have to take a side, we’ll go with the peasants, because they were all going to be in that rising middle class as soon as the King George the Thirds and Pope Something the Seconds got out of their way.

Though we often use it as a shorthand for the Middle Ages entire, the Three Estates was in reality primarily a fourteenth-century phenomenon. You don’t see Geoffrey of Monmouth, Thomas Aquinas, or the Venerable Bede insisting on these three natural divisions of people, ((Aquinas, of course, divided society into a different threesome, “those who have the power” (the nobles), “those who do not” (the commons), and those in-between, the populis honorabilis.)) even though all three were only able to write what they did because of the status afforded to them as card-carrying members of those who pray. Much of the earlier rhetoric of social reform was concerned instead with policing the division of power between just the two groups, the nobility and the clergy; those were the two groups with power to police. Peasants were an afterthought, because who cared what they thought about anything? They were the people who had shit all over them (as someone once put it). But in the fourteenth century times were a-changin’, even if they weren’t a-changin’ into the first draft of Ye Olde Æmæricæ, and the old power relationships were shifting.

Even Reynard would tell you that just because the fox has an explanation for why you're currently on bottom doesn't mean you should necessarily agree that he should be on top.

The pat old explanation of The Plague’s effect on the peasantry still holds an important nugget truth. In the wake of the Black Death there were a lot fewer of those who work around to do the working, and this worried the other thoses. Estimates vary, but it’s not crazy to say that nearly a third of Europe’s population were killed by the plague and that the peasantry was represented disproportionally in that number. In part, those who fight and those who pray were worried because if no one were left to work the fields, then there wouldn’t be any food for anyone, and in part because those left among those who work who might before have worked exclusively in one particular set of fields suddenly found that they might be able to make substantially more working in someone else’s fields, unless their field’s original owners were willing to pony up to keep them. Those who nobody had much given a damn about before so long as they worked now found themselves with some emoticon of power.

The social commentators of the day were, as you might expect, comprised primarily of those who pray, and those who had the good fortune be allowed to both pray and write were still chiefly employed by those who fight. ((Because the fighting they got up to was usually to determine who would control the fields whose output comprised the feudal economic system’s bedrock.)) So when the social order started to change, they filled leaf after leaf of parchment with arguments for and explanations of why those who work should shut up and stop demanding more than they were morally and economically entitled to want. The Estates Literature that flowered was written to enforce an already outdated understanding of how the medieval world worked by those who stood to benefit from the creation of a Good Old Days that left them securely in charge if only they could get everyone to agree to return to it and that explained why The Kids These Days were actually driving Christendom quickly down the road toward Moral Apocalypse. Not long after, those who had money but didn’t exactly have to fight, pray, or work the fields for it followed suit and paid other people to churn out Estates Satire that delighted in pointing out how fat these scribbling monks were, and how lusty the nuns, how girly the knights, how stupid the ploughmen, and even how greedy the merchants and gauche the nouveau riche who funded the satire, because self-effacing jokes that nevertheless smooth over class anxieties aren’t a recent invention.

The way we find those who make public policy and those who chatter on cable television acting toward the Occupiers is, alas, to be expected. The strategy of writing self-serving retroactive social narratives in an attempt to deny real changes in the dynamics of the labor market and the distribution of economic power was likewise not invented this century. But with the Occupiers, we do seem to be trying to out-medieval our medieval predecessors. The debate in America has collapsed the Three-But-Going-On-Four Estates into just Two: those who worked hard and deserve their wealth, and those who ought to just shut up and be happy they can get jobs from those who work. If that seems unfair or overly simplistic, then perhaps someone can explain how that phrase so dear to the most recent crop of Republican presidential hopefuls, “job creators”, differs functionally from “those who are your betters”–which is really what those in the fourteenth century who wanted to be counted among the fighters and prayers meant when they insisted to the workers that they did not deserve the things that led to the Revolt that later bore their name.

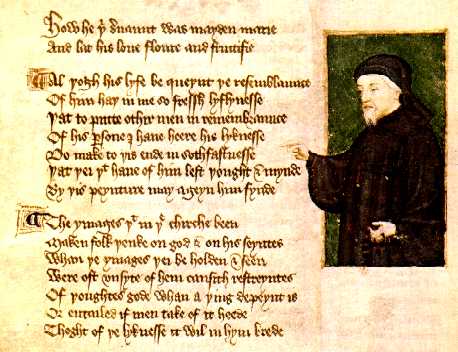

Let me close not with partisan rancor, but with literature. American tenth-graders tend to learn in English class that the weird Chaucer guy who wrote back before people had learned how to spell properly structured his Canterbury Tales around the three groups of pilgrims taken from each of these Three Estates. ((And, for some reason, they’re also told to memorize the opening twenty lines against the unlikely possibility that they should ever run into a medievalist at a cocktail party, where they’ll then be expected to rattle those lines off–and possibly that they’ll earn extra points if they follow the recitation with a remark on how beautiful they find the haphazardly pronounced and poorly remembered verse.)) American undergrads, always eager to reject what they learned in high school, quickly come to believe that Chaucer the ahead-of-his-time visionary was the first person to ever suggest that the Three Estates was a load of crap, which he argued mainly by letting the Wife of Bath talk so much about sex (which no one had ever talked about because of all the religion and piety and such). American grad students, even those without blogs, get handed a copy of Chaucer and Medieval Estates Satire and told to sort it out themselves. ((And also told not to try writing about Chaucer until they’re at least fifty, as all the good work has already been done.)) But I hope the Occupiers heading back to Zucotti have been introduced to at least one other thing about Chaucer.

Those dull, derivative fifteenth-century Chaucerians ((And who I’ve previously insinuated were essentially Chaucerian fanfic writers)) chiefly responsible for giving Chaucer the first leg up that authors need if they ever hope to make it into the canon of a nation’s literature looked to him as “the first finder of our fair language”. Before Chaucer, English was not considered a properly literary medium, at least not among those cash-flush thugs who tended to pay a writer’s bills, even estate-free writers like Chaucer. The English nobility still spoke a fashionable French dialect in court (if not at home) and demanded the French style of verse fashionable on the continent. But for a million reasons, ((That I will not go into for fear of alienating someone whose million-entry list does not overlap enough with my own.)) this, too, was changing in the fourteenth century. Chaucer’s poetry was new and exciting because though he wrote in English he was absurdly cosmopolitan, influenced by the techniques and vocabulary of the great Italian and the not quite as great French poets of his day. And while he would’ve admitted it less freely, he was up on his insular poetic traditions, as well. Under Chaucer’s pen, English imported vocabulary and poetic turns of phrase from far and wide, within and without. He showed those who came after that English was a language worth writing in and gave them the words that let them do it.

The Occupy movement is still waiting for its first finder of fair language, someone to follow the thread of common interest that binds the movement’s fractious disparate agendas and weave it into a cohesive, compelling story. The Occupiers are right to eschew the easy trap of meaningless catchphrase-based protest, but I hope they do not let that aversion keep them from finding the words worthy of the voice that they have fought to cultivate. Until that finder appears, the media will certainly continue to belittle them as a mob comprised only of the entitled, spoiled, lazy, unrealistic, and whatever other pejorative adjectives they wish to make into dismissive collective nouns. True, Occupy has changed the national discourse on debt and inequality, but shouldn’t they now try to change the nation’s discourse about themselves?