As a great man dressed in a mediocre lion costume ((Or, if you’d prefer, a mediocre man in an iconic lion costume featured in an amazing film. I’m not going to force you to validate to my personal obsession with Bert Lahr just to get your permission to quote him.)) once said, “I do believe in spooks. I do believe in spooks. I do I do I do I do I do believe in spooks”, words I bring up because the subject for today is ghosts–though mostly metaphorical ones *knock wood* *salt-over-shoulder*. ((*suspicious glance behind shoulder that doesn’t manage to catch the filthy scarecrow waving its broomstick arms and doing a parody of each unconscious thing you do*))

When last we spoke, I was still going on about this Geoffrey of Monmouth character, but I also promised to finally reveal the cleverest things I think he got up to when writing his Historia, which contained the first full biography of that King Arthur guy you hear so much about these days. ((And by these days, I mean, of course, the last three-hundred and twenty thousand days, starting around the beginning of the twelfth century.)) I promise that in all the posts, I admit, yet every time I go to type that bit up, wouldn’t you know it, a ghost gets in the way. We’ve exorcised a lot of them so far: The Ghost of the Monomyth, The Ghost of Geoffrey’s Critical Reputation, and The Ghost of ‘Accurate’ History, to give them names. ((And for good measure, I even had a go at The Ghost of Christmas Past, who gets off too easy if you ask me. Sure, Scrooge was a job-creator miserly bastard, but barging into a man’s bedroom in the middle of the night is still trespassing, and ferrying people through time and space probably counts as reckless endangerment, if not kidnapping outright.)) At least one more interfering ghost remains, and this last may prove the hardest to bust–nevertheless, let’s strap on the proton packs and hit the Sedgewick. ((No, not that one. (Even I dare not risk the wrath of the mighty one who stands astride the universe’s center.) I might note, while we’re on the general subject, that I wouldn’t need † so many of these explanatory footnotes if you’d only obsessively click all my explanatory links.

† I’d still use them, of course, but I wouldn’t need to.))

At the risk of metaphorical overload, I should admit that today’s ghost goes by the same name as the guy I keep saying my thesis is about, Uther Pendragon. For clarity’s sake, let’s tag him with The Ghost of, to distinguish from the guy who appears in Geoffrey of Monmouth. But the Ghost of Uther is still not quite the right name for our problem, either. Uther’s shady doppleganger is himself just a doppleganger of another ghost, the Ghost of Arthur, a specter who always seems to be hanging out nearby when we catch those faint glimpses of Arthur as pieces of evidence bubble up from the pages of one text or another only to slip through our fingers as we try to pin them down. (([AUTOMATED BLOG WARNING: METAPHORICAL OVERLOAD RISK AT 99.421% AND CLIMBING. ALL USERS ARE ADVISED TO RETREAT TO A DISTANCE OF NO LESS THAN THREE FRAME NARRATIVES AND AWAIT EMERGENCY PERSONNEL. DO NOT–WE REPEAT–DO NOT ATTEMPT TO CONTAIN THE OVERLOAD WITH ADDITIONAL FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE OF ANY KIND, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO ANTITHESIS, HYPERBOLE, METONYMY AND/OR SIMILE.]))

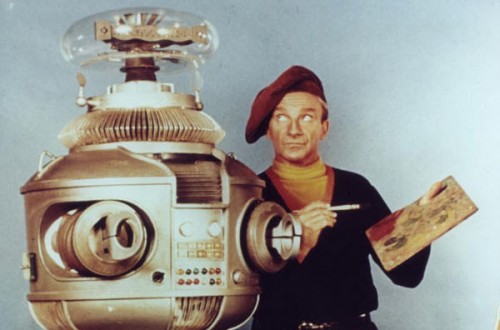

All figures of speech at Got Medieval are monitored by the B9 General Utility Non-Theorizing Artistic License Control Robot (metaphorically, speaking)

So once again, here we are back at Arthur and back to talk of beginnings. I said before that we become acquainted with Arthur by reputation before we are properly introduced to him, because we hear of his name long before we have much of a story to attach to it. These earliest glimpses of Uther’s son that survive in the historical record are so well-known and well-traveled that there’s not much for me to add to them, but for those not up on these things, a quick jot list of early pre-Galfridian Arthur goes like this:

- Around 530ish, Gildas, a northern British monk, writes Concerning the Ruin of Britain (in Latin De Excidio Britanniae), a polemical work that laments the recent conquest of the native Celtic Britons by the Germanic Angles and Saxons and lambasts the Brits for their sins that led to it. Gildas doesn’t mention Arthur by name; ((Though some claim that a character Gildas refers to as “the Bear” is meant to be Arthur, since art– seems to mean bear in Welsh.)) his British are led instead by Ambrosius Aurelianus in a series of (unnamed) battles that ends with the battle of Badon hill, where the British finally lost Britain, circa 480. ((Please don’t pounce on the dates. None of this is exact and all of it is disputed, as I will go into later.))

- Sometime after that, ((The Annals claim they were written contemporaneously, but nobody has reason to believe they were. The manuscripts in which they survive today all date from at least the tenth century. In fact, the rule of thumb for medieval annals is that they’re most likely to have been written nearer to the last entry on their list than the first. Medievals had a tendency to make crap up, as you may have heard, and the temptation to make a contemporary history seem more authoritative by preceding it with a fictional one was pretty strong.)) the Welsh Annals (Annales Cambriae) are compiled, consisting of a series of chronological entries of about one interesting thing that happened in Britain per year, starting in 447. ((There are eight blank entries before the first entry, so you could say starting in 439 instead, if you’re willing to believe that the annalers set out to write a annual chronicle but found nothing interesting to chronicle for nearly a decade. I say†† that’s more likely a masterful touch added by a later forger to enhance the document’s apparent legitimacy.

†† Actually, others say that. I just nod and agree and post it to my blog.)) The chronicle puts the Battle of Badon in 516, turns it into a Welsh victory (it’s ambiguous who won in Gildas’s version) and says that there Arthur carried on his shoulders the Cross of Jesus Christ ((Shoulder and shield look a lot alike in Welsh, so Arthur probably carried a shield with a cross on it, instead of Jesus’s actual cross.)) for three nights. It also notes that in 537 Arthur and Medraut both fell in the “strife/battle of Camlann”. ((A later recension of the text adds a third quasi-Arthurian entry, the Battle of Arfderydd in 573, where Merlinus went mad.)) - A Welsh poem from the seventh century, [Elegies] to [the Men of] Gododdin (Welsh, Y Gododdin, by the poet Aneirin), praises a particular warrior, Cynon fab Clytno, by saying he “fed the black ravens ((That is, he killed people. Then the ravens came by and ate their eyeballs and guts.)) on the ramparts of the fort, although he was no Arthur”.

- As I discussed last post, in the eighth century a monk named who called himself Nennius (but who probably wasn’t Nennius) ((Happens a lot in the Middle Ages. People find a cool text but don’t know who wrote it, so they assign it to the coolest person they can think of who lived around that time. And just as often, people writing a cool text that they don’t want people to know they wrote (usually because they’re lying about all the stuff they say happened and where they say they got the information from) pretend they’re a cool person who’s dead and and who thus can’t call their bluff.)) wrote The History of the Britons (Historia Brittonum), which contains a list of the campaigns of Arthur, twelve battles that culminate in Badon, where Arthur single-handedly killed nine-hundred and sixty Saxons. The cross business is moved to an earlier battle at Fort Guinnion, where Arthur carries the image of the Virgin Mary on his shield (or, possibly, shoulders).

- Around the end of the eleventh or beginning of the twelfth centuries, Arthur appears as a minor character in several Latin saint’s lives, ((The lives of Saints Gildas, Cadoc, Carannog, Goueznou, Padarn and Eufflam, to be specific.)) where he doesn’t come off well at all–sort of an ill mannered bully who can’t keep hold of the girl he loves, the boorish foil to the saintly hero. ((Think Biff from Back to the Future, with the saints standing in for Doc Brown and Marty. Only with less screen time.))

- Probably in 1112, the canons of Laon make their fundraising tour of Britain and report being shown places called Arthur’s Chair and Arthur’s Oven and witnessing the brawl breaking out in Cornwall when someone suggests that Arthur is dead and never coming back.

- In 1125, the historian William of Malmesbury circulates his Deeds of the English Kings (Gesta Regum Anglorum). Though he chiefly wrote his history from the side of Britain’s Anglo-Saxon invaders, when William gets to the British resistance, he allows that the greatest British king of his day, Ambrosius Aurelianus, was able to drive the invaders back briefly, assisted by “the warlike Arthur”, who carried St. Mary’s image at Badon. In an appendix concerning various miraculous sites around Britain, the grave of Gawain is mentioned, along with the note that there is no grave for Arthur, and that many Bretons claim it’s because he never died.

- Around this time (1120-1140), some Italians carved a story about Arthur over the north portal of the Cathedral of Modena. There, a character identified as Artus de Bretania seems to be besieging a castle with some of his knights, including Gawain and Kay. Inside the castle is a woman named Winlogee (who we identify as Guinevere) and a man Mardoc.

You probably have noticed there’s a bit of a gap in that record, then a sudden cluster all at once. After the ninth century, Arthur seems to have dropped off the radar, not popping up again until the beginning of the twelfth, when, as I’ve said before, everyone suddenly got really interested in him again. So where’d he go? For the answer, turn to page 2 when you hear the chime:

[BOOOOOOP]