Each Thursday, I’ll be stringing together some of the disconnected thoughts I’ve had about the subject of my dissertation in a feature I call “Thesis Thursday“. Length continues to be a problem, fortunately for my dissertation’s chances, if not for your chances of getting through Thursday without the risk of eyestrain. This week, at long last, features an appearance by Mr. Uther J. Pendragon himself, the actual focus of my project. Consider yourself warned once more, for

So far I’ve made a lot of noise about Geoffrey of Monmouth, but I worry my point may have been lost in all my enthusiastic asides. ((Which I don’t always have the good judgement to bracket off in a footnote.)) So here’s that point, which also will serve as a quick summary of the first three linked posts, ((Excluding Uther’s Christmas Knight, which would appear much later in my project, after I’ve moved from Geoffrey to introduce the second version of Arthur’s father that arises out of Robert de Boron’s response to Chretien de Troyes’ anxiety about Geoffrey’s Arthurian origins.)) for those joining my series late:

The first guy who tried to write a life history of King Arthur, Geoffrey of Monmouth, fashioned a larger history of the entire island of Britain out of bits stolen shamelessly from everywhere he could in order to find a way to contain the cultural capital that had accrued around the name Arthur by the beginning of the twelfth century. The History of the Kings of Britain was designed as a vehicle by which to transfer that capital to the highest Anglo-Norman noble or ecclesiastical bidder, those who ruled Britain’s multiply conquered ‘native’ British peoples who were, not coincidentally, also the main source of said cultural capital. In return for his effort (and in return for this story we now find so amazing and compelling), poor Geoffrey, then known as Geoffrey Arthur, was rewarded only with a backwater bishopric, a place so lackluster that rebellion and war probably kept him from ever setting foot there before he died. ((When Geoffrey was elected to the office, the bishopric had only been consecrated by the Norman kings for less than a decade. Geoffrey held the post for two years before he died, and the year after his successor was driven from it by Welsh rebels looking to strike at their Anglo-Norman lords. It was sacked and burned half a dozen times in the years that followed.))

This take on Geoffrey is, I admit, kind of anti-climactic, ((As some anonymous soprano remarked in a comment to last week‘s discussion of Geoffrey’s game.)) but that disappointed feeling and the way we respond to it are integral to the way I read Geoffrey’s History. We wish for so much more from the man chiefly responsible launching Arthur’s literary career. ((Launching it in the non-Brythonic literary world, I mean, a qualification I add in hopes of appeasing temporarily the various stripes of Celticists who no doubt consider Culhwch and Olwen (which we will speak of soon, I promise!) and the Welsh Triads to have at least as much claim on Arthur’s success.)) So amazing was Geoffrey’s ultimate success, we are rendered unwilling to accept the more pedestrian explanations, however plausible.

And it would be hard to find a medieval work more successful than Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain, or to finally use the Latin name that my dissertation committee will demand, the Historia Regum Britanniae. Of all the medieval Historiae Somethingum Somethingae or Somithingorum, only Geoffrey’s is accorded the honor of being abbreviated without all that adjectival bric-a-brac; it is, simply, the Historia, even outside the pages of Arthuriana or Arthurian Literature. Though we Arthurians may write of Malory’s Arthur or Chretien’s Arthur, only Geoffrey’s name has birthed a fancy Latin adjective, Galfridian, which we use to divide our studies into pre and post. He is the Arthurian’s terminus ad quem, the point at which no one can any longer deny that we have our legitimate precursor who deserves to be called King Arthur without qualification, no matter how much further a quo any one of us wishes to push his roots.

All this is for good reason. At last count, 217 manuscripts of the Historia remain extant, with fifty-eight of those surviving from the twelfth century alone. Measured solely in terms of these manuscript survivals, Geoffrey’s success rivals even that of Bede the Venerable, who had the benefit of a 400-year head start. And this is not counting all the translations and derivative versions. The Historia was abridged within a decade into a highly influential version by Alfred of Beverley; by the end of the twelfth century it was integrated into the Latin histories of Ralph Diceto and Gervase of Canterbury; and from then on, with a few notable exceptions, it was taken to be the definitive account of British pre-history until the seventeenth-century. Within fifty years of its first circulation it was translated into four Anglo-Norman vernacular versions on the continent: Gaimar’s now lost Estoire des Bretuns, written in the late 1130’s, Wace’s Roman de Brut in 1155, and two other anonymous translations. In the Historia we may find the origins of at least two medieval vernacular traditions, the Brut chronicles in French, English, and Welsh, and the Arthurian courtly romances that collectively come to be known as “the Matter of Britain.” Even minor figures in the Historia’s pantheon of kings of Britain— Locrine, Cymbeline, Old King Cole, Cordelia, and Lear ((You’ve heard of that guy, right?)) —went on to immensely successful literary afterlives. If we are willing to grant Geoffrey a role in inspiring both major strains of the Arthurian tradition, ((And even those who believe that the romance tradition grew out of the independent spread of the Welsh materials to writers like Chretien would have to admit that the Historia nevertheless greatly influenced the material once spread.)) the Historia “generated more imaginative literature than any other text of the entire Middle Ages”, ((Oh, yes, you also have to swipe…er, homage a line from David Howlett.)) and continues to do so today, an unparalleled chain of influence stretching from Wace and Chretien to Fuqua and Zimmer Bradley.

Thus, mindful of this preposterous success, and still gnawed with dissatisfaction from our encounters with the plausible but mundane versions of Geoffrey we can construct from what little we actually know, Arthurians of all stripes ((Or, possibly in this context, Galfridians.)) quest ever onward, further into that terra infirma looking for some sign of what we desperately want to see, a sign proclaiming in blood red gothic typeface, “Here be dragons.” We find no such sign, of course, for none exist, leaving us two options: allow our romantic ideas to go the route of Milton’s or double down. If no aged and crooked warning sign can be found, then dammit, someone get out the red paint and the wood and the antique finish, because there must have been dragons, surely there must. ((Dragons are notoriously uncooperative beasts, yes? Surely their absence is sign of their refusal to cooperate, or else they’d show themselves. So the presence of absent uncooperative beats surely means there must be one around here somewhere… the only way we could be less certain of their existence would be if they cooperated by making us more certain of their existence. Somebody get the History Channel on the line, I’ve got a new series to pitch…)) If we find Geoffrey insufficient, we will simply have to make him suffice. ((Or denigrate him thoroughly before heading out to look for someone else who’ll do better))

We quest for Geoffrey much as we ultimately quest for Arthur. No venal twelfth-century cleric could possibly account for the plenary Arthur whose origins we seek, so we clamor and grasp at each new alternate candidate we find, celebrating then abandoning them in turn, ((Like Republicans grasping at any straw not branded as Romney’s Best.†

† Less popular than Newman’s Own, sure, but they have such a generous return policy. There’s nothing that Romney won’t take back. *boom-tish*)) moving from Artorius to Artognou to Artúr mac Áedáin, desperate for our dragon, for that origin point for Arthur grand enough to contain and account for the uncontainable Arthur whose legend seems so unaccountably important.

And as we quest for Arthur, both Geoffrey and King, so did the twelfth-century quest for him. ((They didn’t so much quest for Geoffrey. They knew where to find him. On his knees in front of the closest Anglo-Saxon with a benefice to assign. *boom-tish* (I’ll be here all week, folks, please remember to tip your waitresses and drive safely.) )) Arthur was the name on everyone’s lips. We find hints of stories about him everywhere we look. Yet though those stories may share some of the same hooks, their dissonances are louder than their consonance. Other than the name, ((And even that varied.)) the only thing the stories and their tellers all agreed upon was that this Arthur was important and vastly so.

In the specific Anglo-Norman historical market which Geoffrey sought to break into, other historians had already tried to account for Arthur’s popularity, primarily by downplaying it, attributing most of the interesting bits of his legend to the stupidity or gullibility of Britian’s natives. Stripped of his fantastic content, this diminished Arthur they then tried to tuck safely away in an isolated corner of Britain’s history, relegating him to a walk on part as a noble but doomed warleader who briefly and unsuccessfully resisted the ultimately successful Anglo-Saxon conquest of Britain, a conquest that had been made irrelevant by the Norman Conquest only half a generation ago. Yet no matter how hard respectable historians tried to contain him, the rumors and stories and wild tales about this Arthur kept multiplying and travelling further.

And so we find our troublesome cleric Geoffrey to be the only one canny enough ((I’ll also accept “desperate enough” or “shameless enough”, if you prefer, but let’s do move past “foolish enough” and “malicious enough”.)) to realize that what the people wanted was not a pigeon hole for the great hero, but rather an origin story that could account for all the things they had heard, the things that made them want to know more. The people wanted their dragon, and Geoffrey was willing to make them one.

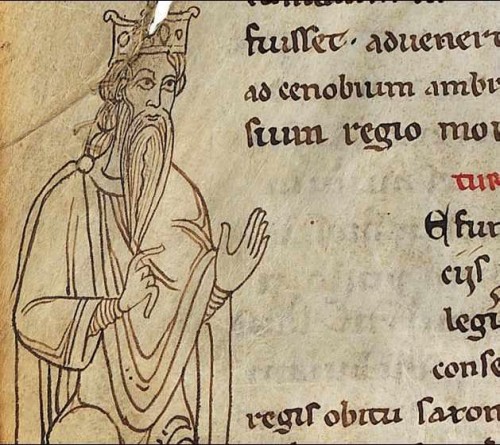

Enter Uther, surnamed Pendragon. At long last, here be dragons.

[CONTINUED ON PAGE 2]

![there-be-dragons-map Here Be [Pen]Dragons](https://www.gotmedieval.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/there-be-dragons-map.jpg)