No snark today, just a few pretty medieval pictures interspersed with thoughts on this whole War on Christmas thing that you hear so much about these days.

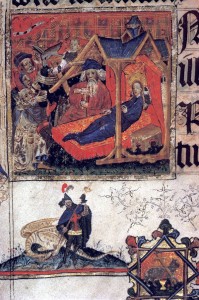

At heart, I think, the War is a matter of incompatible perception. One camp looks at Christmas and sees this:

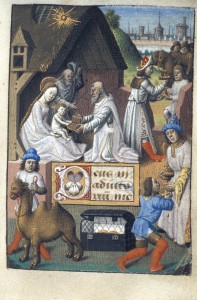

And the other, this:

Behold, a pair of “Adoration of the Magi”. ((The visitation of those three kings… Oh, Rhee, & Tar, I think their names were)) Neither version looks very much like the medieval marginalia this series typically features ((Did you know? Mmm… Marginalia is a series. The 3 M’s stand for Medieval Marginalia Monday†

† And the fourth is a bonus!)) but they both muck about with the page’s margins, nevertheless, so they’re fair game.

The second adoration is actually the most properly called “marginalia”; look closely, and you’ll see there’s a tiny rectangle of text there in the middle of the page, barely a half line of scripture. Everything else–Jesus and Mary, the three magi and their retainers, the gifts, the castle, even the camel–is located fully within the page’s sumptuously decorated margin, a margin that has expanded so as to nearly blot out the page’s text.

Likewise with the first; it’s marginal, if only just. While it’s technically a “historiated initial,” if you squint at the lower left quadrant, you’ll see that the kneeling cup-bearing servant is slipping out into the margin. Everyone else is crowded in so that there’s no room left for him to stand in the main image.

Which one is the metaphor for the Christmas War-Uponers, and which the Christmas Defense Squad?

In the Middle Ages, a story that only worked on one level would’ve been considered a paltry, insufficient thing, hardly worth talking about. Why interpret a text just one way, when you can gloss it five? ((And then set the glosses up in conversation and tell five different stories about what that conversation means.)) I submit that we may benefit from thinking like a medieval Christian for just a little while. ((Their textual generosity was rooted, it must be admitted, in their firm belief that all texts ultimately were meant to tell the same story. Following St. Paul, they believed (or acted as though they believed) that all that was written was written for their (Christian) doctrine. We do not have to share in this to adopt their useful habit of thinking that all texts–and all images accompanying them–are made to teach us something.))

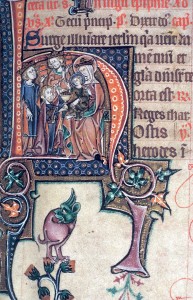

A bonus two-fer image, shepherds abiding and also adoring. (Bonus because my newfound wordiness was rendering the text of this post too lonely)

The aggrieved, inflamed Christian half of this Christmas War ((The side forwarding emails daily decrying fresh outrages done to a nativity scene somewhere-or-other or re-phrased corporate greetings that do not feel properly inclusive)) might more easily see themselves in the first scene. Feeling now suddenly marginalized, they tend to believe that the sanctified part of Christmas is so narrowly circumscribed that their Christmas, the true Christmas, must huddle cramped, a shadow of its former glory.

And the equally incensed and equally righteous secular side ((The ones forwarding a completely different set of emails daily decrying the outrages of newly erected nativity scenes and whatever dumb thing a Fox anchor said about the whole business just today.)) could surely see their plight more readily in the second. Christmas creeps further and further each year, out-stripping what were once its normal boundaries and spilling out all over everything, quashing dissent. Little is left from October to January that isn’t Christmas, they’d say. And while my sympathies lie more with this camp, the medievals would urge me to look still further.

Pointing to the first image again, these hypothetical medievals would also say that the cup-bearer’s foot is out of place, that it has pushed out in the margin where it does not belong, squeezed there by the understandable desire to fill every inch of the picture. The world can only hold so much Christmas before you can no longer tell where Christmas ends and the wider world begins. Both are cheapened in the spillage.

So much text! I banish you with still further bonus images. (Note St. George and the dragon in the margin.)

With the second, they’d remind us not to be so literal. Yes, the figures in the outer margin are Christmas characters, but that does not mean they have to signify Christmas. The true Christmas, the “reason for the season” is more properly represented by the text in the middle of the page.

There, so small you might not see it for the camels, is the holiest word, Deus.

The images and stories around it, all that three kings business in the margin are things we add on top of the true meaning of the text beneath–just decoration, like all those Christmas Trees and Santa sleighs we tack onto the original Christmas holy day to make it into the blander “Happy Holidays”. If you believe in the power of that word, you might feel somewhat threatened by the border hemming it in and thereby pulling focus away.

My two readings is barely better than one, ((Stop correcting my grammar in helpful emails. I claim the Appalachian singular for abstract concepts, even plural ones.)) but I’ll beg off the responsibility for more by admitting but few moderns can keep up with the medieval mind in this regard. And regardless, the images have already shown us something important, whichever camp you’re in. A noisy, overblown margin can block out the center it surrounds, and even small, well-meaning things can spill out into space previously thought inviolate. Which is center and which margin is a matter of perspective.

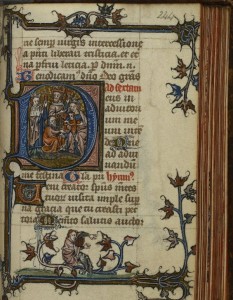

At the risk of pushing my meta-metaphor too far, there is yet more to be learned from our medieval fore-bearers. I know they have quite the reputation for intolerance, and often deservedly so, and also a reputation for getting religion all over everything they touched. But consider this next image, once again of the visit of the magi to the newborn king:

Comparatively restrained, at least by the metric established by the two others, this illumination is not alone on the page. Pan down a bit, and we find a guy in the lower margin doing… well, whatever it is he’s doing:

The weirdness is intentional, as zoom out one step more and we can see the artist added a smaller initial inhabited by a suitably confused-looking face peering downward at the plantward-gesturing cypher:

Zoom out one more stage, and we can see the page as a whole. The holy Christmas gift-giving celebration and the border-baffler are both intended parts of the design, neither detracting from the other, really, just two different things to rest your eyes upon as you scan the book, each rewarding in its own distinct way. The Three Kings, Mary and Jesus do not have to cover the entire page, nor is that marginal man being pushed unwillingly aside.

In the High Middle Ages, page decoration like this was not exceptional, ((Except in that most books were made for people who couldn’t afford such lavish work. But for those that could, this was not a unique style.)) you see it all the time. ((Especially if you come here each Monday.)) Nobody got burned for making books like these until the Puritans got worked up a score of decades later. If the manuscript is well laid out, if the architect of the book has a clear vision, the page can safely hold just about anything, both sacred and profane. Even when it’s Christmas. And even when “just about anything” includes something like the… whatever that is that’s underneath this other version of the holy scene:

Following this image, we might dare, I’d hope, to correct that “even” and say, instead, “especially when it’s Christmas.” Christmas is a roomy holiday. It can contain multitudes. These three kings have nothing to fear from the rowdy margin. They don’t need to spread out to blanket the entire border and evict the oddball, ((The oddball that seems alternately biped and quadruped, depending on how you focus your eyes.)) nor does the oddball represent a first curtailing of their rights that will eventually strip them away entire. The page decoration binds them together in one pattern.

And maybe we can make this marginal oddball our new Christmas mascot, once the War dies down:

Sure beats the heck out of the elf on the shelf.