As you might have heard, Google recently launched the Ngram Reader for Google Books, a tool that lets users search the corpus of texts scanned by Google Books and outputs the results in a handy graph that plots the search term’s frequency in the corpus against the date. Because of the vagaries of OCR, the search engine’s inability to track declension, conjugation, and so on, and the selection bias of the texts that get scanned by Google, the graphs produced by the Ngram Reader should be taken with a not insubstantial pinch of salt. But it’s still a fun tool to mess around with, particularly when it tells you things you already think you know but would nevertheless like to bask in the sciencey comfort of a line graph that tells you them.

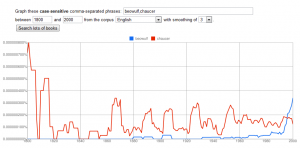

For example, the right-thinking Anglo-Saxonists who I occasionally have coffee with at conferences hate it that Seamus Heaney gets all the credit for popularizing Beowulf for the new millenium. Sure, Heaney’s 1999 verse translation did wonders for early English lit course enrollments, but with the Google Books Ngram Reader we can prove with bi-colored scientific precision that the meteoric rise of Beowulf’s popularity was already underway well before then:

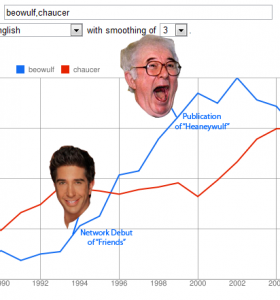

Read it and weep, Seamus. Tables don’t lie. And if we zoom in even more closely, we can pinpoint the exact moment when the wordhoarding Dane shot to popularity:

Again, tables don’t lie. The data demonstrates without the shadow of a doubt that it’s been up, up, up for Beowulf ever since September 22, 1994,** well before the Heaney publicity machine could have plausibly cranked up.***

Another thing the tool is poorly suited to but is still fun to ask it to do is to track the earliest appearances of particular phrases in English. For example, take the phrase “get medieval,” from which this blog takes its title, made famous by Marcellus Wallace in Pulp Fiction. You might think that Tarantino was the first to coin the phrase, but the Ngram Reader tells a different story:

Admittedly, most of those hits are just random concatenations of the words, usually where one sentence ends in get and the next begins in Medieval. Still, the phrase “get medieval” was used before Pulp Fiction with roughly similar meaning at least twice.

The earliest use appears in a 1969 New York Magazine article about home security, “Your Own Defense Budget”. There, Joan Buck writes:

“Some fatalism is appropriate. Brute force can get you into any apartment if you want to get medieval about it. The Fire Department doesn’t worry, for instance, and has a huge battering ram on all its hook-and-ladders, but most burglars won’t go this far…”

Actually, thinking about Marcellus Wallace and battering rams has me wincing in sympathy for poor Zed, so let’s move on.

Google brings up one more pre-Tarantino instance of getting medieval that’s less visceral, but still along the same lines. When characters in Romain Gary’s 1973 novel The Gasp discuss the possibility that their Citroen might be fueled by human souls (SPOILER ALERT: It turns out it is!), they say,

“Nothing but pure science. Let’s not get medieval.”

Though, I suppose it should be admitted that the soul-powered car causes people to worry about getting intransitively medieval, and the battering ram thing is likewise about the author’s own mental state, while the thing that so appeals about the Tarantino turn of phrase, I suspect, is the satisfyingly novel idea of getting medieval transitively, not becoming medieval oneself but doing medieval unto others.

Now after Tarantino’s movie, it appears to have taken a couple of years for “get medieval” to catch on as anything other than a direct quote. It’s not until 1996, two years post-Pulp Fiction that we see things like New York Magazine (them again?!) having a writer “get medieval on a million bits of scarlet shell” as a way of illustrating how hard it is to eat lobster. And even after 1996, when “getting medieval” pops up elsewhere in the Google Books corpus, mostly the phrase is tied directly to Tarantino, one of the actors from Pulp Fiction, or the movie itself.****

By Google Books’ count, it’s not until 1999 that “get medieval” sheds the direct reference and really takes off, and a quick date-restricted search of Google proper seems to confirm that. Hopefully Carolyn Dinshaw won’t mind my pointing out that 1999 is also the year Getting Medieval was first published. By the time we Ivory Tower types finally jump on the meme, you know it’s damn near everywhere. Of course, she could always point back that five years later this blog was born, and according to the chart it’s then that the “get medieval” meme hit its peak and started nosediving, so much that by now everyone just assumes that the name is instead a played-out reference to those milk commercials. But nay, I say thee, nay! Now, don’t you feel ashamed for mixing up your played-out references?*****

—

*8PM Eastern and Pacific, 7PM Central and Mountain, though local listings may vary.

**Though I suppose it’s possible that most of those post-1994 references to Beowulf were contained in sentences like “After failing to get his Friends spec script picked up, noted author Seamus Heaney has decided to tackle a verse translation of the classic Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf.”***

***Possible, but not likely, since everyone knows Heaney’s spec script was picked up and later aired in the 1997 season as “The One Where They Cut Turf (as a Metaphor for the Irish Independence Movement)”.

****In the interim, the forgettable 1997 boxing movie King of the Ring with the tagline “It’s Bound to Get Medieval. Brace Yourself.” and the forgettable Gauntlet clone called Get Medieval.

*****And in truth the blog is probably at least 65% a played-out reference to “Amish Paradise.” So maybe I’m the one who should feel ashamed.