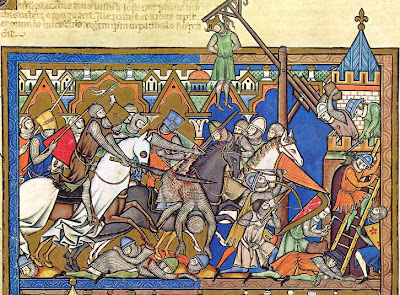

From the Maciejowski Bible, AKA the Morgan Bible, AKA the Crusader Bible AKA the Book of Kings (AKA the Bible so nice they named it twice thrice over and over… ice) comes the only marginal image that I’ve ever seen that should probably be accompanied by a Goofy holler:

And here’s a closeup of our holleree:

A few interesting things to note, other than this catapult operator who clearly skipped the day they covered ‘Step 2’ in catapult operating school.* First is that the illuminator draws in a mound of earth for the overzealous catapulter to have just been pulled off of. That little brown hill is important, because medieval manuscript pages are usually decorated as if the characters on them are subject to gravity’s pull. People can hang out in the vertical margins, so long as they hang off of something, like a a piece of decorated border or the edge of an image. So, the dirt is a key part of the sight gag. Without it, you’d have a different punchline: the man in the margin would be an interloper, like one of those mischievous monkeys, a guy who just happened to come along and grab ahold of the piece of the catapult that’s sticking out of the main image.

The main image, by the way, is of Saul leading the Israelites against Nasash, the king of Ammon, a cruel tyrant who gouged out the right eyes of all the Israelites he could get his hands on, for reasons that nobody’s sure of, but it’s cruel and tyrantish nonetheless. Saul is leading the Israelites in a righteous battle, but not so righteous a battle that the illuminator was worried that a bit of slapstick might be out of order.

I think there’s a little more to the joke beyond simple slapstick, of course (don’t I always?). The illuminator of the Maciejowski Bible is overall fairly strict about the borders of his main images. Like picture frames, this Bible’s borders usually contain the entire subject within them with no marginal overhang.** Almost every time the illuminator lets the image spill out of the frame, however, it’s when the main scene is something bloody, violent, or gory.

Here, for example, is the Maciejowski Bible’s picture of the Israelites sacking Ai and stringing up its king:

And here we have a picture of Saul’s son Johnathon leading an attack against some Phillistines. He’s hardly in the frame at all:

In the images of war, the accoutrements of the combattants (spears, swords, horses, catapults) and their grisly results (beheaded bodies, body parts, spurting blood) simply can’t be contained by the border. Violence is messy; it ruins the lines of the page and spills out into the margins.

Ultimately, I think the illuminator is going for the medieval equivalent of the jerky hand-held camera style that filmmakers use today when they want to emphasize how gritty and real something is. It’s like the part in Braveheart where the blood spatters on the camera lens and a blow knocks the camera back, or like the Normandy invasion in Saving Private Ryan. This illuminator can’t shake the page, so he shakes the images out of the page and into the margins. But in both cases, we have an artist using a momentary reminder of the artificial nature of the medium he’s working in in order to make the whole seem more real.

—

*Step 1: Load the catapult. Step 2: Let go of the shot, for the love of God. Step 3: Fire away. Step 4: Profit.

**Making it hard for me to get a Mmm… Marginalia out of this famous Bible, but look at me go! Incidentally, this is not usually the case. The frame of a medieval image often “belongs” to the world of the picture, not the world of the observer. The images in the picture can lean against the frame, or use it to boost themselves up, or grab it and shake at it like it’s a set of prison bars, etc.