UPDATE 6-21-11: If you just arrived here from Cracked.com’s 8 Filthy Jokes Hidden in Ancient Works of Art, you might be interested in a bit of context on the article.

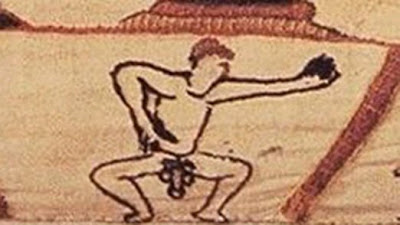

This week, I thought I’d write a bit about a more famous bit of marginalia than I usually tackle. This guy:

A lot of scholarly ink has been spilled trying to explain what this naked guy is doing standing so brazenly in the lower margin of the famous Bayeux Tapestry, right underneath a woman and a clerk who are labeled “ubi unus clericus et Ælfgyva,” or (loosely translated) “Look here! It’s a clerk and Ælfgyva”:

Clearly, there’s something interesting going on here. Ælfgyva is the only named woman in the entire Tapestry,* and there’s a naked guy standing right under her with his little naked guy standing out for all to see. But just what is going on is a question that has divided scholars for a long time.

It would help if we could figure out who Ælfgyva is supposed to be. Her name means “Elf-Gift,” which is a pretty name used for lots of Anglo-Saxon women, including those who are also called something else. I think it must have been the medieval equivalent of how hip dudes in the 1950s used to call all attractive women “Kitten.”** Some scholars with better eyesight than I can see a hint of a pink veil over her face, so many, many brides and bethrotheds of various Anglo-Saxon and Norman nobles have been suggested over the years. None of these bridal candidates, however, quite explains the naked man under her. So other scholars, looking for a lady a touch more naughty, have suggested various mistresses of other Anglo-Saxon and Norman nobles.

The problem with the mistress angle is that none of them have anything to do with the story being told on either side of the mysterious robed woman. Immediately before Ælfgyva and her clerk we have William and Harold meeting at court after William secures Harold’s release from Guy of Ponthieu, a Norman noble who captured Harold after his ship was run aground in his territory. On the other end, immediately after the mysterious lady, the Tapestry turns to William and Harold riding out together to scourge Conan (not the barbarian, sadly) and the rebels in Brittany, a Norman province.

It’s fairly clear to me that we are meant to take Ælfgyva as a part of the same narrative chunk as the meeting. The scene is flanked on either side by castles, which, in the Tapestry-maker’s visual lingo, means that it’s all one piece.

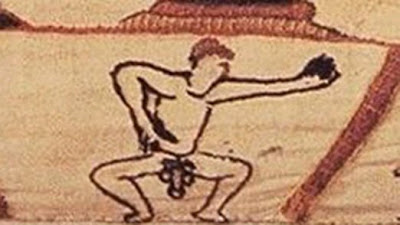

So that brings us right back to where we started, our conspicuously naked marginal man. Or, should I say “men”? If we zoom out a little more in the picture, we can see that there’s another naked guy immediately before Ælfgyva’s, this one holding an adz (the image should expand if you click it–it’s kind of thin, I know):

And now let’s zoom in on our naked adz-wielding man:

In addition to being an excellent Scrabble word, an adz (or adze) is a tool for smoothing down wood. According to Wikipedia, the user of an adz usually stands astride the wood being smoothed and pulls the adz towards him, exactly the sort of motion one would not want to make while naked, if you ask me. The potential for self-Bobbiting is, I think, clear, and also suggests to me the beginnings of an interpretation of the two naked men in question that, to my knowlege, nobody else has suggested.***

I believe we are meant to see the man using medieval power-tools in close proximity to his junk as handy shorthand for Harold’s state of mind in the scene above. At this point in the Tapestry’s story, Harold has pretty much jumped out of the proverbial frying pan and into the less proverbial sharp blade near one’s danglies. Guy of Pothieu, the man who first captured Harold, was just a minor noble who had the good fortune to own the territory that Harold’s ship got shipwrecked upon. When Willaim subsequently comes along and buys his freedom, Harold is suddenly beholden to a much more powerful man. Negotiating his way out of that mess is going to be tricky. Perhaps as tricky as woodworking while your willy is hanging out.

The second naked marginal man, on the other hand, has his legs parted and his willy on display, as if to say, “Hey, look at me! I managed to use that adz without becoming a castrado, thank you very much!”**** And what do you know, in the next scene, Harold has managed to talk his way out of his predicament. He now rides out with William as an ally to fight Conan.

Explaining why Ælfgyva is relevant to this bit of fast-talking on Harold’s part is a little harder. Maybe the veil-spotters are right, and Harold just betrothed one of his sisters to William (or betrothed himself to one of William’s sisters) in exchange for his freedom.

—

*I suppose an optimist might say that clearly women are more important than men to the Tapestry’s architect, since a full 50% of them are named, as compared with the much smaller percentage of named men. The only other woman depicted in the Tapestry is a mother leading her child away from the thatched-roof cottage that the looting Norman knights have just burninated.

**Or so Hollywood has led me to believe.

***That’s right, kids, this post is veering into “Actual Scholarship™” territory. I apologize to the readers who come here exclusively for monkeys with trumpets on their butts. Hey, at least he’s naked, right?

****”Also, I have this smooth board, if anyone’s interested. And what do you mean you don’t want it if touched my Tom Johnson? Don’t be so square, daddio.”*****

*****Also, the naked guy is from the ’50s. Weird, I know.

Recent Comments